Selecting the Best Construction Contract

Selecting the right contract for your development project can have a substantial impact on the success of your project. However, more importantly, the contract sets the tone for the type of relationship you wish to create between your firm and the general contractor you have selected. We highly recommend reading our article on power parity prior to this article, as this can influence one’s thinking on the subject. Attitudes we see too often amongst our developer clients which may negatively impact their contract selection are as follows:

Many developers have legal backgrounds. While this can be an advantage for understanding the nuances, potential penalties, various contract mechanisms or other key legal concepts, it can also lead to an attitude that a perfect contract will ensure all risk has been mitigated and a positive outcome should be guaranteed. This is, unfortunately in our experience, flawed thinking. While a solid contract may clearly outline penalties to the general contractor because of sub optimal performance, remember our position on power parity. We have seen far too often a general contractor fail to perform, and upon seeing that the developer may try to leverage penalty clauses to then work harder on documenting how delays or cost overruns were not their fault than on completing the project. While this documentation may be, if not erroneous, stretched truth, it may have sufficient reasoning to hold up in an arbitration. Keep in mind that, unless the developer is willing to dedicate full time staff to the project, a general contractor will always have a documentation advantage over the owner’s representative (and often doing so will be too late to properly document initial delays or cost overruns which led to the initial dispute). The last outcome any developer should desire is allowing a project dispute to result in litigation. Projects which head in this direction will suffer additional cost overruns, schedule delays and there is no guarantee that the developer or his investors will be made whole after a protracted legal battle.

Many developers presume that the general contractor will act in bad faith and push for a one-sided contract that provides them with greater perceived authority or methods to punish the general contractor. While we cannot state that all general contractors are saints, we have experienced several very bad actors, this type of attitude is highly counterproductive. Again, a thorough understanding of power parity can be illuminating. If a developer pushes for an aggressive contract, this will not go unnoticed by the general contractor. While a developer may be able to take advantage of such a contract on one project, this may result in a burned relationship, or worse, a poor reputation in that market which can negatively impact the developer’s ability to do further projects in that location.

Many developers have had poor experiences on past projects with one or more general contractors. This can lead to lessons learned which may lead to proprietary language a developer may draft for inclusion in further contracts which is often a positive outcome. However, it is critical that a developer take an unbiased hard look internally at the root causes for these negative outcomes. Were they truly the fault of the general contractor? Might the issues have been related to actions or inaction by the developer’s team (not all permits in hand at the start of construction, significant delays by consultants in providing answers or solutions to RFI’s, unanticipated site conditions, etc.). Some developers are quick to blame the general contractor for the poor outcome of a project when the issues may have been avoidable had the developer’s team been more proactive.

Generally speaking, the developer should spend far more of their time and effort on finding the right general contractor and vet them thoroughly than on assuming any general contractor with whom they work is a bad actor and that they should assume they will be screwed.

In our experience, the most equitable contract to help establish a good relationship between the developer and the general contractor is the Guaranteed Maximum Price or GMP contract.

Advantages of a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) Contract:

Cost Certainty: The GMP provides the developer with a guaranteed maximum price for the project, offering certainty in budgeting and financial planning.

Risk Allocation: The contractor assumes the risk for any cost overruns beyond the GMP, incentivizing them to manage costs efficiently and control project expenses.

Incentive for Efficiency: Contractors have an incentive to complete the project within or below the GMP to maximize their profit margins, which can lead to increased efficiency and cost savings.

Transparency: The GMP contract typically requires contractors to provide detailed breakdowns of costs, promoting transparency and accountability in project finances.

Reduced Change Orders: Contractors have an incentive to minimize change orders and scope changes that could increase costs, as any additional expenses may come out of their own pocket beyond the GMP.

Disadvantages of a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) Contract:

Initial Cost: Contractors may include contingencies in the GMP to mitigate the risk of unforeseen expenses, potentially resulting in higher initial costs for the developer compared to other contract types.

Scope Limitations: Changes to the project scope or design may be limited under a GMP contract, as any modifications could impact the agreed-upon price. This can reduce flexibility for the developer during the construction process.

Risk of Disputes: Disputes may arise between the developer and contractor over what constitutes a change in scope or who bears responsibility for certain costs, potentially leading to conflicts and delays.

Potential for Overestimation: Contractors may err on the side of caution when setting the GMP, leading to overestimation of project costs and potentially higher expenses for the developer than necessary.

Complexity: Negotiating and administering a GMP contract can be complex, requiring careful attention to detail and clear communication between the developer and contractor to ensure mutual understanding of expectations and responsibilities.

Despite these potential disadvantages, a well-structured GMP contract can provide significant benefits in terms of cost certainty, risk allocation, and transparency for both developers and contractors involved in construction projects.

A few additional comments on this contract type:

While some developers have the attitude that all “shared savings” should belong to them as it is “their money,” this attitude both violates our concepts of power parity and also removes from the general contractor much of the incentive to obtain the best possible price from their subcontractors. Therefore, it is recommended that the shared savings always be set at 50/50. This helps to create a feeling of equal partnership between the two firms and their respective teams.

It is also critical that developer’s never count shared savings as their money until the end of the project. Often a project will build some shared savings “contingency” during the buyout process, as the team finds unexpected lower bids amongst subcontractors, material savings, etc. Developers are often tempted to say, “well we did so good on the buyout, I want to spend my portion of the savings on upgrades to get a better product.” This is flawed thinking. Often and invariably, there will be unexpected costs which arise later in the project which are unanticipated. For instance, one of those cheaper subcontractors may go out of business before starting their work (likely because they were underbidding all of their jobs). This must be made up for in the budget later by selecting the second lowest bidder (and costs may be even higher as the new subcontractor was not locked up at buyout). The general contractor might also need to pay a subcontractor overtime to ensure a project maintains schedule. Therefore, it is best to track shared savings as its own contingency line item but empower the general contractor to utilize it as they see fit until the project reaches conclusion.

Transparency is a huge advantage on this type of contract, specifically for obtaining subcontractor level data. That said, a traditional GMP is designed to provide transparency over the general contractor’s own internal costs as well. This includes the 10-15% of the contract which makes up their general conditions (project overhead), insurance and fee. While auditing these costs may be prudent on extremely large jobs, it is recommended that they be treated as lump sums for smaller projects (or auditable only in the case of significant delay, cost overruns or litigation). Why? First, to ensure the developer’s team is focused on areas of high importance (delivering the project on budget and on schedule). Second, to preventing a souring of the relationship by demanding mercurial documentation which has a minimal impact on the final outcome. Example: On a $50M job, we might expect that general conditions may be ~6% of total costs, or a budget of $3M. The project will run with a full-time on-site crew of five people for two years. Assuming an average pay package (salary + benefits) of $200K each, this will already eat up 2/3 of this budget. In addition, there will be the added costs of trailers, office supplies, equipment, etc. Let’s assume the general contractor runs the job extremely well and spends only $2.9M of the general conditions budget. If the GMP is based on a 50/50 split, theoretically, the developer would be due half of these savings, or $50K. Will this $50K turn a bad project into a good one for the developer? Unlikely. If the general conditions go overbudget, will the developer be happy to see a change order for the overrun? Nope. In fact, the best way for a general contractor to save money on general conditions is to finish the project sooner, which is highly beneficial to the developer and his investors. Therefore, rather than insisting on the $50K due, it is often better to be magnanimous an allow the general contractor to make more money on a well-run project.

Aside from a Guaranteed Maximum Price (GMP) contract, there are several other major types of American Institute of Architects (AIA) construction contracts commonly used between a developer and a general contractor:

Lump Sum (Fixed Price) Contract (AIA A101):

Advantages: Provides certainty regarding project costs since the contractor agrees to perform the work for a fixed price. Simplifies budgeting and financial planning for the developer.

Disadvantages: Contractors may include contingencies in their pricing to mitigate the risk of unforeseen expenses, potentially resulting in higher initial costs for the developer. Limited flexibility for changes in scope or design.

The Lump Sum is often the favored contract for the developer’s “deal guy.” Most deal people believe they will get the best possible construction number for their proforma by hard bidding every project using a lump sum contract. This is flawed thinking which often results in the worst possible outcome. First, hard bidding 80-85% of a total project’s costs to the lowest bidder under an opaque contract is highly risky. While the upfront number may work great in the proforma (and for which there is often a slight discount to GMP), this both sets up an antagonistic relationship between the general contractor and the developer but also incentivizes the general contractor to pass along as many change orders as possible. Always keep in mind the true cost of a project is not the starting number, but the number at which the project ends.

The lump sum (fixed price) contract can be perceived as carrying higher risk for the developer due to several factors:

Cost Overruns: In a lump sum contract, the contractor agrees to perform the work for a fixed price. If the actual costs exceed the agreed-upon lump sum, the contractor typically bears the financial burden. However, if the contractor underestimates the costs or encounters unforeseen expenses during construction, the developer may face cost overruns that they are not contractually obligated to cover.

Limited Flexibility: Lump sum contracts often provide limited flexibility for changes in project scope or design. Any modifications to the project may result in additional costs for the developer, as they may need to negotiate change orders with the contractor, potentially impacting the project budget and timeline.

Quality Control: Since the contractor has agreed to perform the work for a fixed price, there may be incentives to cut corners or use lower-quality materials to stay within the budget. This could compromise the quality of the final product, leading to additional costs for the developer to rectify any deficiencies.

Contractual Disputes: Disputes may arise between the developer and the contractor over what is included in the lump sum price and whether certain items or services should be considered as additional costs. Resolving these disputes can be time-consuming and may involve legal proceedings, leading to delays and additional expenses for the developer.

Market Fluctuations: Lump sum contracts may not account for fluctuations in material prices or labor costs that can occur over the course of the project. If there are significant increases in costs due to market fluctuations, the developer may bear the risk of these cost increases if they are not explicitly addressed in the contract.

Overall, while lump sum contracts provide certainty in terms of project costs upfront, they also transfer significant risks to the contractor. However, if the contractor encounters difficulties or underestimates the project's complexity, the developer may ultimately bear the brunt of these risks, making it potentially the highest risk option for the developer.

Cost Plus Fee with GMP Contract (AIA A133):

Advantages: Offers flexibility for changes in scope or design during construction. Provides transparency regarding project costs, as the developer pays the actual cost of construction plus a fixed fee to the contractor.

Disadvantages: Can result in higher costs for the developer if the project exceeds the agreed-upon GMP. Requires careful monitoring to ensure that costs are kept under control.

Construction Management Contract (AIA A201):

Advantages: Allows the developer to engage a construction manager (CM) who acts as an advisor throughout the construction process. CM can provide expertise in project planning, scheduling, and coordination.

Disadvantages: Can result in additional management fees compared to traditional contracts. Requires close collaboration between the developer, CM, and general contractor to ensure effective communication and coordination.

Design-Build Contract (AIA A141):

Advantages: Streamlines the construction process by combining the design and construction phases under a single contract. Encourages collaboration between the design team and the construction team, potentially leading to cost savings and faster project delivery.

Disadvantages: Limited control over design decisions for the developer, as the design-build contractor is responsible for both design and construction. Requires careful selection of the design-build team to ensure compatibility and expertise.

Each type of contract offers different advantages and disadvantages, and the choice depends on the specific needs and priorities of the developer, the complexity of the project, and the level of risk tolerance. Consulting with legal and construction professionals can help developers select the most appropriate contract type for their project.

What about the Integrated Project Delivery contract?

The Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) contract is a collaborative approach that involves the owner, architect, contractor, and sometimes key subcontractors working together from the early stages of the project to achieve common goals. The key with any IPD contract is to involve the General Contractor and critical subcontractors as early in the process as possible, with the understanding that their portion of the work will not be competitively bid. This may, in some cases require paying General Contractors and subcontractors a pre-construction fee to reimburse them for their invested time. Under any such arrangement, it is also critical to clearly communicate to all participants, General Contractor, subcontractors and consultants, a clear mission that they are each responsible to work as a collaborative team to get the project executed. Such contracts are often more advantageous when the project has little risk of uncertainty (a corporation or institution has decided to build a new building on an existing campus for a specific function, for example). It is also critical to convey any hard criteria that must be met by the team in order for the project to be executed (maximum budget, delivery schedule, etc.).

Advantages:

Collaborative Environment: Promotes collaboration and integration of expertise from all project stakeholders, leading to better decision-making and problem-solving.

Shared Risks and Rewards: Encourages all parties to share in the project risks and rewards, fostering a sense of shared responsibility and alignment of interests.

Early Involvement: Involves key stakeholders, including the contractor and subcontractors, in the early stages of design and planning, leading to more efficient project delivery and potentially cost savings.

Innovation and Value Optimization: Facilitates innovation and value optimization by leveraging the expertise of all project team members to identify and implement best practices and value-added solutions.

Improved Communication and Transparency: Promotes open communication and transparency among project team members, reducing misunderstandings and conflicts.

Disadvantages:

Complexity: Implementing an IPD approach requires a significant investment of time and resources to establish collaborative processes, contractual agreements, and governance structures.

Risk Allocation: Requires careful negotiation and agreement on how risks and rewards will be allocated among project team members, which can be challenging and may require innovative contractual arrangements.

Legal and Insurance Issues: Traditional legal and insurance frameworks may not align well with the collaborative and integrated nature of IPD, requiring adaptations and potentially increasing complexity.

Culture Shift: Requires a cultural shift in how project stakeholders traditionally approach construction projects, which may require education, training, and change management efforts.

Coordination Challenges: Requires effective coordination and communication among all project stakeholders throughout the project lifecycle, which can be challenging, especially in large or complex projects.

Overall, the Integrated Project Delivery contract offers significant potential benefits in terms of collaboration, risk-sharing, and value optimization but requires careful planning, coordination, and commitment from all project stakeholders to be successful.

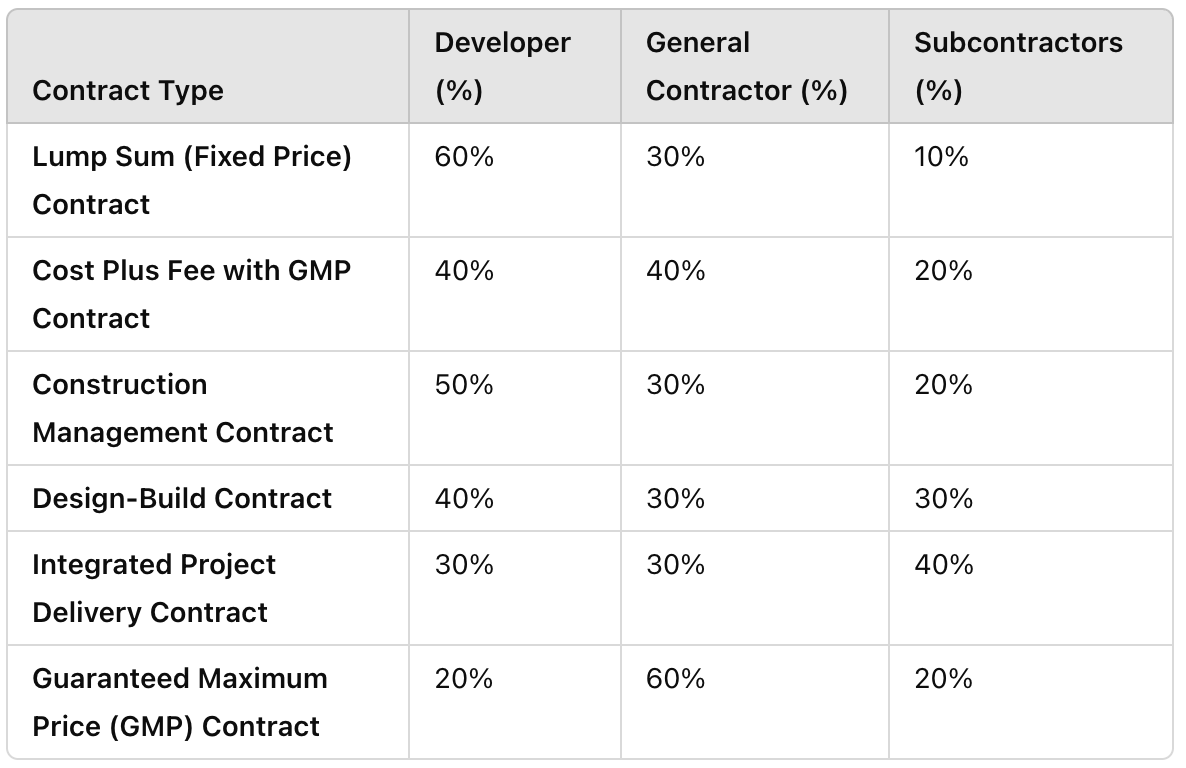

For an alternative way to assess the correct contract for one’s needs, the following is an approximate breakdown of the allocation of risk between the Developer, the General Contractor and the Subcontractor for each of the six contracts discussed above. It is important to note, however, that no matter the contract type, a failure by the General Contractor ultimately places the Developer at full risk for any project. This is why vetting a General Contractor is so critical.

It may surprise Developers that the often most popular contract, the Lump Sum, which many believe delivers the lowest possible price and transfers ultimate pricing risk to the General Contractor would be the riskiest overall to the Developer. Reasons for this are as follows:

Cost Overruns: In a lump sum contract, the contractor agrees to perform the work for a fixed price. If the actual costs exceed the agreed-upon lump sum, the contractor typically bears the financial burden. However, if the contractor underestimates the costs or encounters unforeseen expenses during construction, the developer may face cost overruns that they are not contractually obligated to cover.

Limited Flexibility: Lump sum contracts often provide limited flexibility for changes in project scope or design. Any modifications to the project may result in additional costs for the developer, as they may need to negotiate change orders with the contractor, potentially impacting the project budget and timeline.

Quality Control: Since the contractor has agreed to perform the work for a fixed price, there may be incentives to cut corners or use lower-quality materials to stay within the budget. This could compromise the quality of the final product, leading to additional costs for the developer to rectify any deficiencies.

Contractual Disputes: Disputes may arise between the developer and the contractor over what is included in the lump sum price and whether certain items or services should be considered as additional costs. Resolving these disputes can be time-consuming and may involve legal proceedings, leading to delays and additional expenses for the developer.

Market Fluctuations: Lump sum contracts may not account for fluctuations in material prices or labor costs that can occur over the course of the project. If there are significant increases in costs due to market fluctuations, the developer may bear the risk of these cost increases if they are not explicitly addressed in the contract.

Overall, while lump sum contracts provide certainty in terms of project costs upfront, they also transfer significant risks to the contractor. However, if the contractor encounters difficulties or underestimates the project's complexity, the Developer ultimately bears the brunt of these risks. In addition, if the business relationship between the Developer and General Contractor is weak, such as in the case of only working together on a single project, the General Contractor will likely attempt to shift risk back to the Developer through the change order process.

Contingencies and Allowances

Finally, it is critical that Developers fully understand the use of Contingencies and Allowances.

A contingency is an amount of money set aside in the project budget to cover unforeseen costs or risks that may emerge during construction. These risks might include unexpected site conditions, design changes, or unforeseen delays, such as weather or labor shortages. Contingencies provide a financial buffer to ensure the project can continue smoothly despite these uncertainties.

An allowance is a pre-established amount of money included in the contract for a specific item or scope of work that is not fully detailed at the time the contract is signed. Allowances are used when the exact cost of certain work or materials cannot be determined at the time of contracting, but an estimated cost is included to allow for progress.

Another way of putting this is that an allowance is a budgetary amount set aside for a known unknown (such as dynamiting rock in the construction of a foundation where testing has revealed rock exists on the site, but the extent cannot be fully determined until the site has been fully excavated) where a contingency is for unknown unknowns (any completely unanticipated cost increase, such as a subcontractor going out of business and needing to be replaced by the next highest bidder). It is also critical that the Developer clearly identify these either on the General Contractor’s side of the budget or on their own. By placing contingencies on the General Contractor’s side, it is made clear that the General Contractor may use these funds under the qualified conditions as outlined in the contract. In such cases, it is critical that the Developer or their Owner’s Representative review, but not second guess, a General Contractor’s right to apply for use of these funds. Unlike Contingencies, the use of allowances on the General Contractor’s side typically require approval by the Developer or their Owner’s Rep. Therefore, it is important to be wary of replacing hard bids for a portion of the work with associated known unknown risk (such as excavation) with a smaller contract and an allowance. This may be advocated by the General Contractor or even a misguided Owner’s Rep to (theoretically) reduce costs, but it returns the full risk of any such known unknown to the Developer. Conflicts over the use of allowances can often lead to poor relations which are ultimately counterproductive to the success of the project.

While every project is best served by the right contract with clearly outlined provisions making sure maximum risk is either correctly identified, assigned, and mitigated, the Developer is best served by expending at least as much energy on developing a fair and positive business relationship with the General Contractor to ensure that the puntative elements of the contract never need be utilized.